Watch out, newbies – contains Portal plot spoilers.

In a sense, the reason Portal’s GLaDOS is such a great villain is that she’s an utterly terrible one. Convinced of her superior intelligence, and believing her rat run of a testing laboratory inescapable, she fatally underestimates the player from the off. And when come-uppance looms, she greets it about as gracefully as Donald Duck greets a custard pie to the face.

Where System Shock’s SHODAN remained a thing of menace right to the bitter end, Valve’s spin on the notion of a rogue Artificial Intelligence soon descends into farce. Powerless to halt your advance on her central computing cores at the heart of the Aperture Science centre, GLaDOS wheedles, jokes, cajoles, threatens and taunts – part HAL 9000, part spoiled child. Defeated but undeterred, the jumped-up answering machine trumpets her survival in the form of a brilliantly awful closing pop song, styled like a credits reel and accompanied by crude little scraps of ASCII art.

The Half Life developer seems to be gearing up for similarly hilarious reversals in the cooperative segment of Portal 2, set hundreds of years later. The new stars, two mute Cyclopean robots reminiscent of Laurel and Hardy, are even more contemptible in the eyes of their mistress than Chell, the first game’s human test subject. They’re built to spec, coded to obey, distinguished by the colour of their giant irises alone, easily replaceable, utterly expendable. GLaDOS’s disdain is evident. As she puts it in a trailer, “You don’t know pride. You don’t know fear. You don’t know anything. You’ll be perfect.”

It’s hard to make out much of the dialogue amid the uproar of a publisher showcase, but what we do pick up soon gets us giggling. “How can you fail at this?” GlaDOS erupts after we accidentally tip Blue-bot into a vat of lethal silicon syrup. “It’s not even a test.” Later, she points out that we’re not in competition with our skinny, orange-lensed colleague, but that if we were, we’d be losing. But we’re not. Valve’s comic Muse is as quick on her feet as ever.

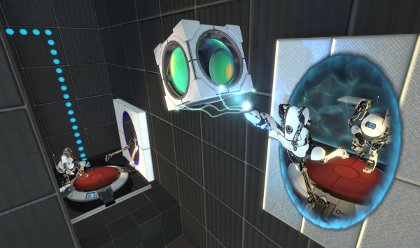

Each bot is equipped with an Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device, aka the portal gun, and the pair must overcome a series of spectacularly abstract test chambers – offering twice the gameplay hours of the original’s scanty single player mode. As before, the guns create wormholes between white-tiled surfaces: you squeeze one trigger to place an entrance, the other to place an exit. Most of the early conundrums and their solutions are familiar – one of the first scenarios asks you simply to connect portals to reach a high ledge.

By the third chamber, however, you’re already doing crazy stuff with the technology, positioning portals above one another to create bottomless shafts, building momentum in free-fall, then re-situating the upper portal on a nearby ramp to slingshot yourself across a chasm. A subtle onslaught of environmental cues and some acerbic commentary from GLaDOS keep things reasonably transparent, though it’s safe to say that you’ll take to the game more naturally if you’ve beaten its predecessor.

Mandatory teamwork alters the balance of play significantly. Perspex windows, portal-cancelling force fields, mechanised grills and dirty great blocks of concrete ensure that not all the puzzle pieces are within reach of each participant. You’ll need a strong rapport with your partner if you’re to prevail, and some sturdy communication tools to boot. Valve can’t do much about the former, but they’ve certainly come through with the latter. Waypoints can be placed by clicking a stick, should yelling orders into your headset mic prove insufficient, and portals now come in four fetching shades, so you won’t confuse yours with those of your minion/accomplice.

Bots aren’t the only objects that can move through portals, of course. Crates cry out to be transported to pressure panels, laser beams to be refracted through surfaces – perhaps to charge an energy node, or incinerate a machine gun turret (the latter still talk, and yes, they still sound like possessed Barbie dolls). Using a handheld prism cube to pivot the beam, you might also zap your co-op buddy for kicks. It’s all about sharing the love.

Which is presumably why the developer’s built in an emote system. It’s an oddly clumsy, charmless feature, requiring that each player hold a button and roll a stick to the same option in tandem, for no other pay-off than a cutaway shot of a hand-slap or chest-bump (rather jarring, coming from the famously first-person-centric Valve).

But then, one suspects that awkwardness and arbitrariness are the point – what better way, after all, to express so paradoxical a concept as empathy between machines? If nothing else, the fact that GLaDOS finds these displays of affection irritating indicates that there’s more going on here than meets the eye. We’re looking forward to finding out where the game will take the idea – to say nothing of the separate, six-hour solo mode, Chell herself or her new computer buddy Wheatley – when it hits shelves in April.

When in April? Why, the 22nd if you’re European, the 18th if you’re North American, and the 21st if you’re an Aussie.

Satoru Iwata Video Interview - the late Nintendo president spoke with Kikizo in 2004 as 'Nintendo Revolution' loomed.

Satoru Iwata Video Interview - the late Nintendo president spoke with Kikizo in 2004 as 'Nintendo Revolution' loomed. Kaz Hirai Video Interview - the first of Kikizo's interviews with the man who went on to become global head of Sony.

Kaz Hirai Video Interview - the first of Kikizo's interviews with the man who went on to become global head of Sony. Ed Fries Video Interview - one of Xbox's founders discusses an epic journey from Excel to Xbox.

Ed Fries Video Interview - one of Xbox's founders discusses an epic journey from Excel to Xbox. Yu Suzuki, the Kikizo Interview - we spend time with one of gaming's most revered creators.

Yu Suzuki, the Kikizo Interview - we spend time with one of gaming's most revered creators. Tetris - The Making of an Icon: Alexey Pajitnov and Henk Rogers reveal the fascinating story behind Tetris

Tetris - The Making of an Icon: Alexey Pajitnov and Henk Rogers reveal the fascinating story behind Tetris Rare founders, Chris and Tim Stamper - their only interview? Genuinely 'rare' sit down with founders of the legendary studio.

Rare founders, Chris and Tim Stamper - their only interview? Genuinely 'rare' sit down with founders of the legendary studio. The History of First-Person Shooters - a retrospective, from Maze War to Modern Warfare

The History of First-Person Shooters - a retrospective, from Maze War to Modern Warfare